Measuring crop temperatures

In greenhouse cultivation, we normally measure the greenhouse temperature. However, the temperatures of the plant and fruit are also very important in achieving optimum production and quality.

Many growers already work with an infrared crop temperature meter which is connected to a climate computer. This enables them to build up a good understanding of the temperature of the top of the crop. The readings are subsequently plotted in graphs and compared with, for example, the greenhouse temperature and incident radiation.

There are also other possibilities for measuring the temperature at various places in the greenhouse and at different heights in the crop, for example using a hand-held infrared meter. These meters vary from simple models for measuring at one spot to advanced equipment that can measure temperature variations over a large surface area.

How does an infrared thermometer work?

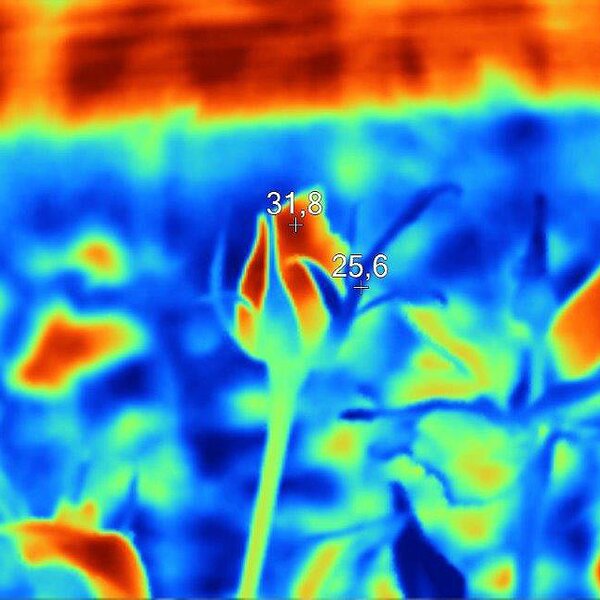

Everything on earth radiates infrared light, which is detected in the form of heat. The warmer the crop, the more infrared light it radiates. An infrared thermometer measures the strength of the radiation between 7,500 and 13,000 nanometers. The hand-held meter converts this value and displays it as a temperature. A professional thermal imaging camera also displays these temperatures as a normal photograph of the crop in a gradation of colours. Affordable thermal imaging cameras have recently come onto the market which can be mounted on a smartphone. The resolutions of these cameras are fairly similar to those of professional cameras and they are consequently suitable for measuring the temperatures of crops.

Picture: measuring crop temperatures using a professional thermal imaging camera

Why is it important to measure crop temperatures?

Direct incident radiation may cause the temperatures of plants and fruit to rise considerably in localised spots because the plant collects more energy than it can process by photosynthesis. The plant has various ways of processing this superfluous energy, but these methods all have their limits. If the plant receives excessive radiation, it may burn. Measuring the temperature of the crop with a thermal imaging camera clearly shows that large temperature differences can arise, both vertically and horizontally.

Based on this information, decisions can be taken regarding the closing of shading screens, application of a coating to the roof, or alteration of the position of the vents with regard to the sun. Diffuse light improves the vertical and horizontal distribution of light and, furthermore, crops are less likely to burn at a specific light intensity if the light is diffuse. There is, however, always a risk that, despite the use of a diffuse coating or diffuse glass, the incidence of direct light through the vents on clear days will cause fruit and leaf burn.

This can be avoided by closing the shading screens far enough to prevent direct light from falling on the crop or by closing the vents relative to the position of the sun.

Plant and fruit temperatures will, generally speaking, be lower with diffuse light than with direct light. This has advantages in summer because excessive temperatures can lead to crops burning. In spring, with diffuse light, the temperature of the crop may be much lower than that of the greenhouse itself, which can be detrimental for the growth rate and production. So keep an eye on the temperature of your crop and, if necessary, raise the greenhouse temperature in the morning and/or ventilate less during the day.